GST, three initials that dominate a much wider reform designed to protect lower income households

This summer the States will decide on the biggest shakeup to the tax system in nearly two decades.

At the heart of it is how to raise an extra £50m. a year, money needed, it is argued, to fund major building projects at schools, the hospital, the ports and beyond to keep the island functioning.

Broadly speaking, what the States brings in through taxes and charges is in balance with what it spends on delivering the services it currently supplies - so the deficit is in paying for the infrastructure.

That £50m. figure, which is more than what the island spends on the entire Home Affairs budget, is disputed, with some believing that there are major savings to be made in how the public sector operates, others that there are other ways to pay for things.

On Monday, details of what the GST package would look like, including mitigations to leave people on lower incomes better off and unprecedented restrictions on how it can be changed in the future, were published.

Those three initials sparked an almost instantaneous backlash.

But there are some qualifications needed here.

A parallel workstream looking at alternatives based around corporate taxation has yet to deliver any recommendations, so this is a debate with half the information.

The GST package may never be needed, and it is still subject to change in the States through an upcoming debate, which is the next step in the process.

After that, in June, both it and the as yet unseen alternative will be on the table.

Broadening the debate

One of the biggest dangers to an informed public debate is there being too narrow a focus on the individual elements that make up these packages.

It is something Policy & Resources vice-president Gavin St Pier is all too aware of as he is faced with the task of getting a broad, at times complicated, picture across.

“This Policy and Resources Committee could only ever recommend any form of consumption tax if it was part of a package which has significant mitigations for those on lower incomes,” he said.

“Unless you've taken all that on board, then inevitably you get distracted by those three initials [GST] and you don't take the debate any further. It's a real challenge.”

The principle mitigation is a reduction in the standard rate of income tax from 20% down to 15%, which will apply from the point above someone’s tax free personal allowance up to £32,400 in today’s terms.

At the moment, people also pay social security contributions on every pound that they earn.

This proposal would introduce a social security allowance.

It would also introduce an annual payment, the Essentials Cost Relief Payment Scheme, for low-income households who are not on Income Support but are still vulnerable to price increases, such as pensioners with savings but low monthly incomes.

To qualify, a household must have a gross income below £32,400, and there would be a £520 payment annually for a single adult or £860 for a couple.

Usually, the States pension and income support are adjusted every January based on historic inflation data from the previous June.

To prevent a delay where pensioners and benefit recipients struggle with higher prices for a full year, the proposal would bring forward these increases to coincide with or slightly precede the GST launch in early 2028.

“When you take all of that into account, not only are you able to raise a net £50m for the public finances as a whole, but actually many households are better off.

“In particular, broadly speaking, if you're earning up to £50,000 a year, you will be better off under this package than you currently are.

“Currently, you'd be paying around about £10,000 pounds in social security and income tax. After this package, you'll be paying about £8,500 a year. That's a significant benefit.

“The other thing that I think is lost in this debate is the realisation that of that £50m. raised, 60% of that actually comes from non-Guernsey household sources. In other words, it comes from companies, particularly from the financial services sector, by the introduction of an international services exemption, which is part of the GST system, and it comes from the visitor economy, from those visitors who come and consume in our community.

“So as a way of increasing the tax base without increasing the burden on the Guernsey household, that is a significant opportunity.”

Its still important to note that for those middle to high income houses, things will get noticeably more expensive.

Targetting financial services - the Jersey way

Jersey pioneered the International Services Entities Scheme, designed to gain an increased tax contribution from the financial services sector under its GST, while minimising the administration for both businesses and the government.

Without a scheme like this, international financial services, the bedrock of the local economy, would generate no extra revenue.

That is because under international norms, services provided to clients outside of Guernsey are "zero-rated," meaning no GST is charged to the client. However, without an ISE scheme, these firms would still incur GST on their local expenses, like rent or electricity, and would need to file hundreds of quarterly returns to reclaim those costs.

Instead of the "charge and reclaim" cycle, eligible businesses would be able to choose to pay a fixed annual fee, which would vary depending on their size.

It is expected to raise some £10m to £12m. in fees, but will be expanded beyond what Jersey does to include the international insurance and e-gaming sectors.

“This is, in essence, a very straightforward scheme, you basically just pay a single flat fee to take you out of all of that administrative burden,” said Deputy St Pier.

“It's clearly worked for the best part of nearly two decades now in Jersey. For us, we think it would raise between £10m and £12m, which is a significant additional contribution from the financial services sector, which has been part of the call when considering tax reform, ‘what else can the government do in terms of ensuring that there is a fair contribution from our corporate sector?’ And I think this is one way of doing it, in a way which clearly has proved to be acceptable in a very comparable jurisdiction.”

To tax food or not?

The decision about whether to charge GST on food has sparked a passionate debate already.

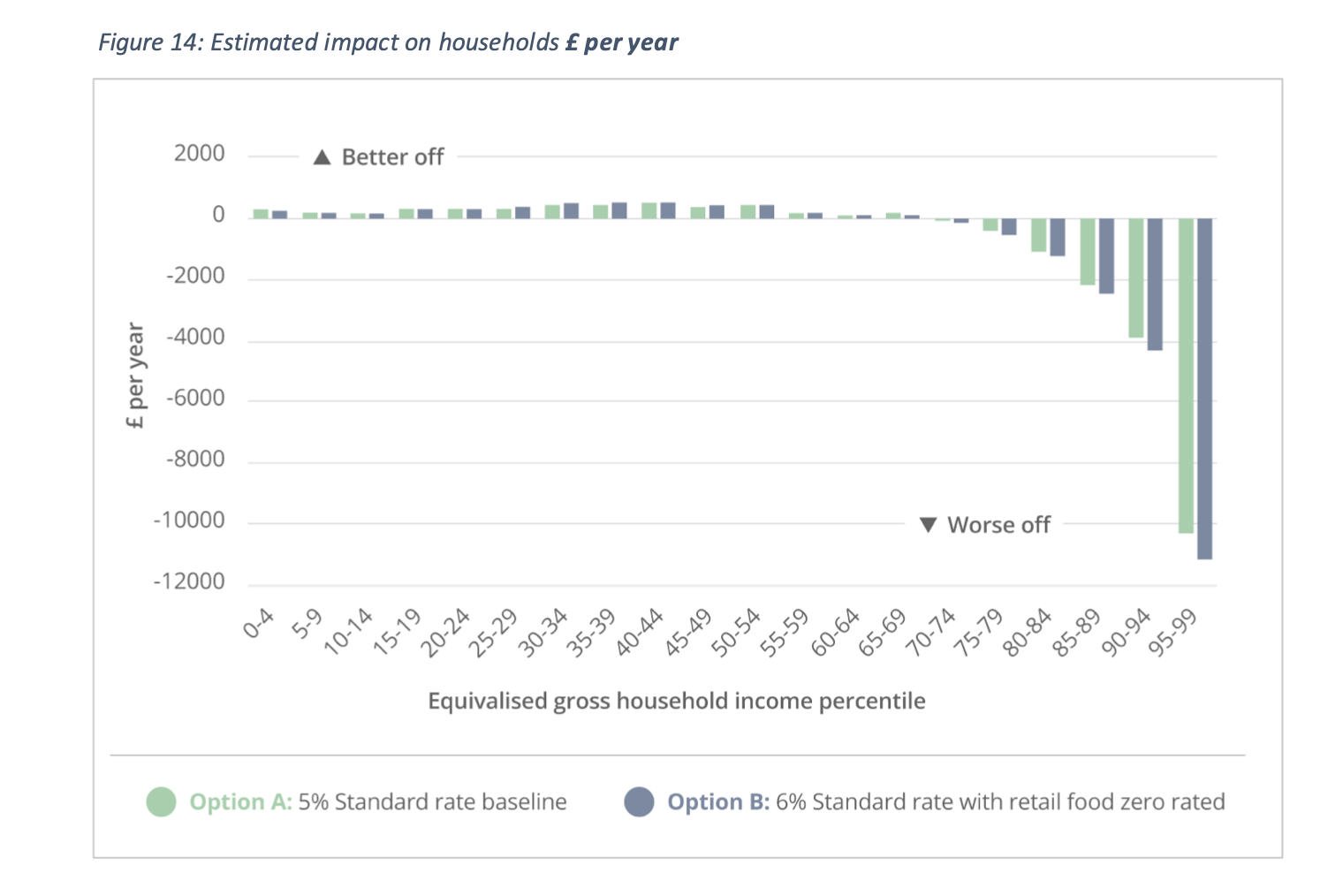

Including food means that the rate can be set at 5%, excluding it would mean increasing that to 6% to generate the same amount of money.

One of the factors behind P&R recommending, if a GST was introduced, that food would be included was about keeping the system simple for the retail sector.

Also, the more exemptions there are, the higher the basic rate needs to be, which is partly why the UK has a VAT at 20%.

“The other factor, which is counter intuitive to most people's expectations, is the realisation that actually the lowest income households are actually worse off with food being outside the scope of GST.

“That detailed analysis really requires you to think about how households are consuming, house by house. That's the kind of work that's been done, is to understand consumption patterns.”

About £8m. would be lost in revenue generation by zero-rating food.

One example given in the report is that lower income households spend a high proportion of their income on other taxable items like energy, clothing and household goods.

The 1% increase on these non-food items often costs these households more than what they save by not paying tax on food.

But it is a complex picture.

P&R also argues that zero-rating food is poorly targetted because the wealthy gain more from it.

The Committee's modeling of the lowest income quartile (the poorest 25% of households) shows that 28% of these households would be worse off by more than £5 a month if the States chose a 6% GST without food. 23% would be better off by more than £5 a month under the zero-rated model.

For the remaining households, the difference between the two options is less than £5 a month in either direction.

A tax on education?

The decision on what to exempt from a GST is political, and while P&R has proposed a package, it is now up to members to see what levers they want to pull to balance things out.

Private education would be subject to GST under P&R’s plans, exempting it would add 0.1% to to the headline rate to keep income levels the same.

“The reality is, you're saying, ‘well, actually, all other consumers will have to pay more in order to compensate for those who are paying for private education’. That's a political judgment call, really, and that ultimately is a decision the States will need to make.”

“Once you start down the road of deciding that something should be exempt, then there will always be a case for something else. It comes back whether you want to stick with the principle that in order to keep it low, you keep it as simple as possible and broad based as possible.”

Locking in mitigation measures

One of the concerns that always surrounds GST is the perception of how easy it would be to simply ramp the rate up once it has been introduced.

P&R is proposing some unique measures to guard against what might happen in the future, all with the knowledge that the next States could rewrite the rule book as it wishes.

It would put into law that if there is a future increase in GST, then there will need to be compensating increases in the mitigation measures - so the pension benefits, the rates of allowances, the essential payment scheme and so on.

The committee also believes that it is worth considering having a super majority measure, where there would have to be a two-thirds majority vote of States members in favour of a rate change.

“That doesn't mean it won't happen or can't happen, but it seeks to adequately address the argument that this is an easy change.”

The GST package is being brought forward now because should the States go with it in June, there are tight timelines to get all the measures in place.

A slip back a year means missing out on £50m. of income.

There have been some very well publicised problems with the revenue service IT transformation already before introducing a new tax, with Deputy St Pier was the messenger for only last month.

He acknowledged the concern, but offered assurances.

“GST as a system of taxation, is not unique,” he said.

“Guernsey would not be trying to create something bespoke, which is often where projects do go badly wrong, when you're trying to do something special and different.

"Actually it is a very, very tried and tested tax model, and all the systems that go with that are obviously in use all around the world. So I think that should give us some reassurance, but I don't underestimate it at all, and I'm not seeking to diminish the importance of an effective implementation.”

Comments ()