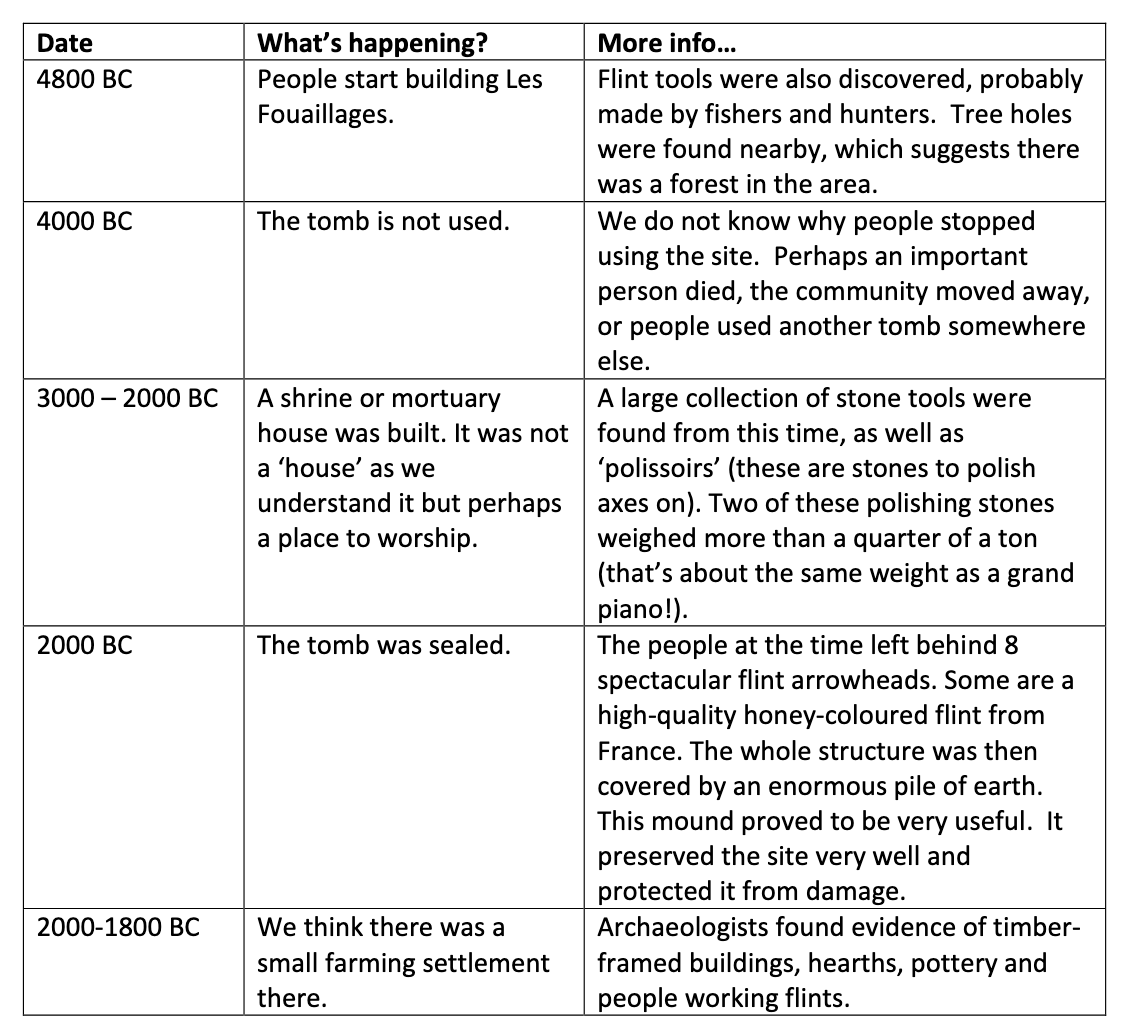

Dig This: Piecing together the story of Les Fouaillages, one of the oldest monuments to the dead

Coincidences. Happy coincidences.

That sandstorms swept across Guernsey after the Roman period ended.

That a German excavator during the Occupation stopped digging.

That a gorse fire in the 1970s revealed a clue.

That a couple walked past and had the skills to spot something unusual.

That is just a short tale of how Les Fouaillages survived through some 7000 years and came to be rediscovered.

The burial site is believed to have been created in about 4800BC, one of the oldest monuments to the dead.

For perspective, it outdates Stonehenge and the great pyramids of Egypt.

It sits on L’Ancresse Common, a small information board giving a brief insight into its importance and the most regular visitors the golfers teeing off blissfully unaware of the significance of what they stand next to.

The assuming nature of Les Fouaillages is perhaps why it is not in the public consciousness as much as Le Dehus, with its rare local example of prehistoric art, or La Varde higher up on the common (which in 1811 was discovered by soldiers, also under sand). You cannot walk inside.

But the protection offered by being buried helped preserve a remarkable legacy, more than 36,000 finds of pieces of pottery, stone tools and flint.

Among them were eight spectacular flint arrowheads left behind in around 2000BC when the tomb was sealed.

There are things experts have pieced together about the site, but a huge number of questions remain which renewed efforts in the past couple of years and modern technology are starting to answer.

John Lihou says he discovered Les Fouaillages in 1976 by a “series of happy coincidences”.

As a child he was interested in archeology, becoming well versed in the work of Frederick Lukis and his sons who excavated dolmens including La Varde, Le Dehus and Le Trepied in the 1800s.

“I was walking across the common with my late wife, and we came across an area of burning.

“If you're interested in archeology, areas of burning are always good for having a scratch around.

“And the first thing that struck me was that there were two granite boulders, possibly half a meter, a meter across, which were next to each other, and one of them was one sort of granite, and the other one was another sort of granite.

“So although you get outcrops on the common which might suggest that there's just a natural rock coming out, one of those had been taken there, and the implication is that they were part of an old structure. There was very little to see.”

He helped make arrangements with La Societe Guernesiaise for an initial controlled dig, a two metre strip down the side of the earth mound, which happened two years later.

“There is a defining curb of stones, relatively small stones that run all around the monument, very big at the beginning, but as it tails off, they get smaller. And there it was, and between the stones, flints, between the stones, prehistoric pottery. It was a clincher.”

What followed was more serious excavations led by Ian Kinnes from the British Museum, which began in March 1979 to produce prolific finds. He said it was the first long mound discovered in Guernsey.

Two more springtime digs followed, revealing details of a site that was used and abandoned in phases. Initially it was built by those who lived on hunting and fishing in the late Mesolithic period, then left from about 4000BC. It is thought a shrine or mortuary ‘house’ was built by the first farmers of Neolithic times, in a phase that lasted from around 3000 to 2000BC.

The tomb was sealed in 2000BC, covered in earth.

In very broad terms that is what is known about the monument, but there is a huge amount of information that has never been formally written up and more to be done on what settlements were in the surrounding area.

“There's a long history which we're hopefully now finally starting to address of it not being published, which is something that happens in archeology time and time again,” said States Archaeologist Phil de Jersey.

“It's great fun digging sites up, but actually it takes an awful lot longer to write up what you find. And it was a very complicated, complex excavation. There was a huge quantity of finds. The figure is something like 36,000 pieces of flint and pottery. It was an unusual site for Guernsey.

“It was the kind of site we hadn't had before and wasn't particularly well known from the neighboring bits of France, and you have an excavator who comes in from outside, has the funding for three week excavation seasons, but then is back in the day job the rest of the time.”

Because of the destructive nature of archaeology, the record is paramount.

Not as much progress had been made in writing up the work as had been expected. Kinnes died a decade ago.

In the last couple of years more people have got involved in France and Britain, allied to John going through the original source material, to bring everything together and hopefully give Les Fouaillages the prominence it deserves.

More than stone

By the time Les Fouaillages was first built Guernsey had been an island for the best part of 4000 years.

The exposed L’Ancresse would have been scrubby, with much of the island forested with large trees. The sea levels were still slowly rising.

One of the bigger picture general debates is how the transition from hunting to farming occurred, and how it spread north from Europe into Britain.

The islands are both at the heart of that and uniquely positioned because of the surrounding waters.

Ideas, goods and stone were coming in by water, probably from the Cotentin Peninsula of northern France, people potentially travelling by dugout canoes.

That forested landscape would change as the ability to cut down trees came with the transition to farming.

One of the reasons for more recent interest in the site by researchers in Brittany is about getting more information from the environmental evidence, something which was not available when the original excavations happened.

“Historically, there always tends to be a bit of focus on the monument,” said Phil.

“But in more recent years, archeologists have generally tried to broaden that, to look around the monument as well.

“When Kinnes excavated, he did actually excavate an area adjacent to the tomb as well, which did have Bronze Age settlement.

“Ironically, having put a couple of trenches in last year, nearby, we actually found a 12th century AD settlement fairly close to Les Fouaillages, which was rather unexpected.

“This little 12th century building is about two meters down in the sand. But obviously it was viable back then as a place to live. It reinforces the thing that we've always got to remember, it's true for L’Ancresse, it's very much true for the north end of Herm, what else could be buried underneath all that sand?”

Most of the evidence for those sand blows in Guernsey is that they happened in the Medieval period.

The sand protected the site, but it was also a draw for the Germans during the Occupation.

Some very big claw marks showed up on some of the stone during the first excavation, signs that a steam shovel had been at work - and a narrow escape.

36,000 fragments of the past

Part of the story of Les Fouaillages is of flint, stone and pottery.

The noticeable missing element is human bone.

Most flint in Guernsey is poor quality as the only natural source is from beach pebbles.

But the eight small arrowheads that were used when the tomb was closed are beautiful, four made of amber coloured flint, four of them darker.

The former likely came from Le Grand-Pressigny, south in the Loire Valley of central France, the latter from Normandy, near Caen.

“They would have been made as votive offerings,” said John.

He believes the same is true of a small polished handaxe that was also discovered, which although of good quality, would have been of little practical use.

“Something that was made to represent the past and put it as a votive offering to the ancestors.”

There is a parallel, perhaps, between the shape of Les Fouaillages and the shape of an axe.

“We do get imported stone axes occasionally, but the local stone is actually very good for the production of polished stone axes,” said Phil.

“There's certainly several from the Les Fouaillages and hundreds from the island as a whole. So clearly, even if they had to import the nicest flint, they were able to manufacture locally some very fine, polished stone axes.”

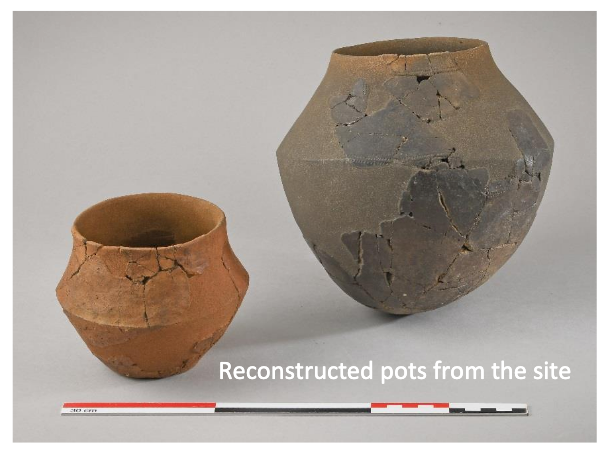

Two pots have been reconstructed which belong to the first phase.

La Societe Archeological Section Secretary Tanya Wells said they were a type of pottery well known from continental Europe, but unusual here and very rare in Britain.

“The sort of thing that hopefully will come out of this new exercise is what proportion of the pottery from the excavation is of that nature, because quite a lot of it might turn out to be later as well, as you've got this very long period of use of the monument right into the Bronze Age.”

Unless you have got something diagnostic on the pottery sherds, she said it was quite difficult to say whether you were dealing with an early Neolithic piece of pottery, or one into the late Neolithic or Bronze Age.

“[When you have] patterns or enough of a piece of pottery to show the shape or form of the vessel, then you can start to talk about the time period. But if you're dealing with lots and lots of little bits, that's tricky.”

Clues can come from analysing small inclusions of stone that were used to temper the pots, it could show sandstone or limestone which are not found here.

A lot of the pottery is expected to be locally produced.

One find not among the 33,000 pieces from the funerary site is human bone.

It is likely to have decayed away long before the sand would have blown in and protected it.

“It means that one of the big unknowns is how many people were buried in this monument,” said Phil.

“We just don't know anything about them. And also the size of the settlement, or the size of the population around it. This is something that we just don't get the information from.”

There are hints.

The stones of Les Fouaillages are small when compared to say the 30 tons capstone of Le Varde, capable of being moved by a handful of people.

“This is one of the things that differentiates it from the later dolmans,” said Phil.

“This sort of earliest phase of monument building could be done with a relatively small population.

“You're certainly not having to get a couple of 100 people in to try and drag some massive stone up the hill.

“One thing that fascinates me is how it was organised, because you're obviously in a society where the only means of communicating is face to face, talking to someone. There's really no other option. So when you do start needing a few dozen people, or a couple of hundred people, you need to arrange a time when you're going to do this, and who's going to provide the food?”

One way could have been by times of the year, observing sunrises, sunsets and the phases of the moon.

Usually the entrances of the big megalithic tombs are aligned with the equinoctial times of the year in spring and autumn.

Les Fouaillages is out of alignment with the other stone monuments in Guernsey, along a North North East direction.

“It's one of the little mysteries of it,” said John.

Taking the story forward

The work on Les Fouaillages is an international effort.

When Ian Kinnes retired from the British Museum he moved to Normandy.

Material from his digs were taken to France for archaeologists, who were familiar with it, to work on.

Among them were Helene Pioffet-Barracand, who studied the pottery for her PHD.

She maintained her interest and managed to secure some French government funding a couple of years ago to start looking more at the context of the Les Fouaillages and the area around it.

“Another person who needs to be named and thanked is Alison Sheridan, who is now a retired curator from National Museum of Scotland,” said Phil.

“Alison has a very long, distinguished publishing history of looking at early Neolithic settlement up the Atlantic Coast of Scotland, Orkneys, Isle of Man, down to the Channel Islands. And she was also a good friend of Ian Kinnes and his widow. And it was really Alison who, I think, actually said to Ian's widow Barbara that she would get Les Fouaillages published.”

That publication is imminent.

A lot of the written archive is in Edinburgh, while the material archive and the drawings from the digs remain in Guernsey. John is now back in the Guernsey Museum assisting Allison’s work.

“However good the records are, and often they're not great, to actually understand a site as the person who directed the excavation is really difficult,” said Phil.

“And with a site as complex as Les Fouaillages, that is really quite a challenge, but someone like Alison is one of the few people who could do it, just because of her huge knowledge of that period.”

Those archives could hold the answers to some practical questions.

“For example, were all the stones, even the biggest ones, completely moved [during the excavation]?” said Tanya.

“If they were, that's a shame, because there are now techniques where you can do luminescence dating of sediments underneath the stones and get dating it that way, which people weren't thinking about in the 1970s.

“But how do we find out if all the stones were moved? You would hope that it would be somewhere in the archive, particularly in the site books and the site records that were kept of day to day working, but until you go through it all you don’t know. Even then you might not find out, because they might not have bothered to mention that.”

Also more imminent is the results of soil analysis from recent work.

Why it matters

Les Fouaillages is a special site for many reasons.

One of them is because it was built at the very start of a change in thinking and practice.

“We don't really know what people did with their dead in the Mesolithic,” said Phil.

“One of the defining features of the change to the Neolithic is people start to monumentalise where they're burying their dead.

“And Les Fouaillages is one of the very earliest examples of this in Guernsey, but in a much wider landscape as well.

“It's really exceptionally rare to get burial mounds that early in this part of Northwest France. For me, that's one of the key features about it, because here's one of the first places that these early farmers, early settlers, were actually something changed in their culture and society that they started marking the place where they were burying their dead.”

The longevity of its use inspires the imagination, said Tanya.

Were people living nearby?

“Maybe they weren't living there, maybe they were coming and still leaving offerings there?”

We will never know the memories and stories being passed down through the people that used the site, but we can think about how our own history, churches, rituals and people behave, she said.

“A lot of archeological sites have that aspect, but Les Fouaillages has it really, really strongly, because it embraces such a very long time period, and it has these complex phases of use that hopefully the publication will one day untangle beautifully with lots of diagrams and reconstruction pictures of what it was all like.”

Nearly five decades ago John discovered the site.

The revitalised interest means he may finally see some more answers.

“I'd sort of given up, mentally, that ever it would ever get published,” he said.

“It takes a certain amount of resources, certain amount of funds, but also a certain amount of expertise. It couldn't be done by me or anybody here. So we've always relied on help from the mainland, and very often from universities, but in this case, from the museum services in Britain.

“I'm really looking forward to the fact that it will ultimately get published after 50 years.”

Comments ()